Harun Farocki, for example, has explored the changes in working processes in contemporary societies and the way these are represented in line with the parameters of the dominant visual culture. This is reflected in his latest project, in collaboration with Antje Ehmann, Labour in a single shot, currently on show at the Tàpies Foundation. The fruit of a workshop carried out in 15 cities of the world, based on an investigation into the subject of “Labour”, brought together a series of videos, of 1 or 2 minutes long, with a single shot, that reflected different forms of work in the world, remunerated or not, material or immaterial.

The subject gives rise to much discussion, particularly now that we are witnessing how, due to the post-capitalist pressure of the “markets”, labour rights are at a very low ebb, and how if a remedy isn’t found soon human rights will also begin to be called into question, under a barrage of arguments revolving around security and sustainability. Hence, it was a bit disappointing to establish that the current edition of Manifesta, taking place these days in Zurich that proposed the suggestive title “What people do for money?” remained a not very incisive proposal. One in which, yes, work was undertaken in the context. The thirty artists invited to develop new projects did collaborate with specific professionals resident in the city of Zurich and also with different schools of architecture and film. But, the ambiguities and conflict that a subject like this (labour-money-selling yourself-power) could lead to, be it from a critical or prospective stance failed to appear.

More profound was the analysis proposed by the VI Jornadas Filosóficas de Barcelona, ccoordinated by Xavier Bassa and Felip Martí-Jufresa. These sessions explored the history of labour and the disciplinary domination of capitalism or, in other words, the “salaried slavery” that Noam Chomsky has explained so well.

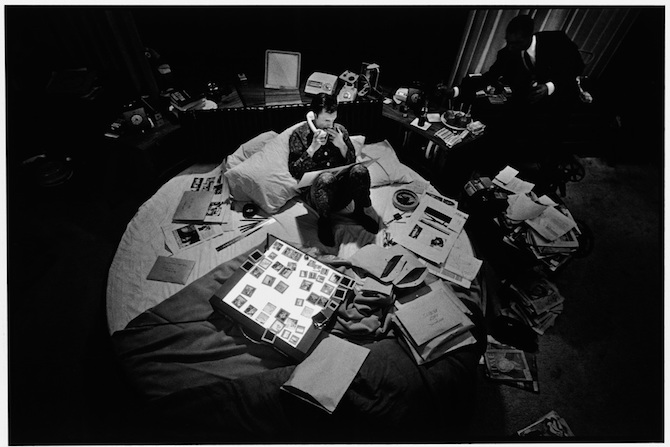

But where were we? The architect and professor at Princeton, Beatriz Colomina talks about to be permanently connected and available, in sleep mode but always alert and prepared to switch into on mode, converts us into “voluntary prisoners” into professionals whose office ends up overlapping with the place of rest. The bed, where we remain hyper-connected, predisposed to interrupt our sleep at 3 in the morning if necessary to have a videoconference with Brazil or China, to later carry on sleeping. Colomina, who focussed on the study of architecture in relation to the media, sees a quite peculiar antecedent for this form of life: Hugh Hefner, the creator of Playboy. Whose rotating bed became the place from where he constructed his economic empire and also the centre of his mansion. A bed not precisely for having sex with the playmates so much as a place of control, equipped with a fridge, hi-fi, telephone, archives, bar, microphone, dicta-phone, headphones, television, breakfast table, desk and remote to control the lights. According to Colomina: “The post-war era inaugurated the high-performance bed as an epicentre of productivity: a new form of industrialisation which was exported globally and had now become available to an international arm of dispersed but interconnected producers. A new kind of factory without walls was constructed by compact electronics and extra pillows for the 24/7 generation”.

In his book 24/7. Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, goes further, observing how the supermarkets open 24 hours seven days a week and the global structure that sustains them, which exemplify non-stop production and consumption, are on the point of uniting with the human subject. “24/7 is a time of indifference, against which the fragility of human life is increasingly inadequate and within which sleep has no necessity or inevitability. In relation to labour, it renders plausible, even normal, the idea of working without pause, without limits. It is aligned with what is inanimate, inert, or un-ageing. As an advertising exhortation it decrees the absoluteness of availability, and hence the ceaselessness of needs and their incitement, but also their perpetual non-fulfilment”. The future Crary envisages is terrifying, based on scientific studies (stemming from the observation of the white crown sparrow that passes days without sleeping to leave its nest ready) aimed to be applied in a military environment (there’s a pressing need for a sleepless soldier): “as history has shown, war-related innovations are inevitably assimilated into a broader social sphere, and the sleepless soldier would be the forerunner of the sleepless worker or consumer. Non-sleep products, when aggressively promoted by pharmaceutical companies, would become first a lifestyle option, and eventually, for many, a necessity.”

And if we return to pose the question “What do people do for money?” no doubt the answer would be “anything and for little money”. Enslaved and precarious. How can artists indicate, reflect and respond to this situation? How do artists today confront the impositions of the political and financial powers? What are the ambiguities? These are the questions that were raised in the exhibition Yes, I Can! Un portrait du pouvoir, curated by Sébastien Planas at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Walter Benjamin in Perpignan and these are the responses or comments the artists offer: Franco within an urn, camouflaged by ballot papers (Eugenio Merino), two riot police executing a careful choreography (Carlos Aires), an arm, a penis and a crow as the “passions” that motivate all actions (Taroop & Glabel), a combination of iconic images and popular texts on the value of money (Claire Fontaine) or the protest phrases written on walls and later erased such as, “An ignorant populace usually chooses an ignorant government” (Adrian Melis). How is criticism established? How to be part of the political, financial, military and religious system and at the same time maintain freedom? Is it possible to remain between resistance and submission?

Andrea Fraser is another of the artists who knows how to play well with ambiguities and contradictions. She herself has embodied and interpreted the different roles, voices and hierarchies of the agents of the art system. Her conclusion is clear: “It is not a question of being against the institution. We are the institution. It’s a question of what kind of institution we are, what kind of values we institutionalise, what forms of practice we rewards and what kind of rewards do we aspire to.”

The exhibition in Arts Santa Mònica, celebrating the ten years of the Sala d’Art Jove, in some way, endeavours to identify certain discourses and common threads, to elaborate a sort of photo-fit image and summary of the emerging art scene in Barcelona of these last ten years. It identifies as one of the most significant subjects that of professionalization, a reflection on work, the work of the artist and work in contemporary societies. A good example is the installation Quiero Trabajar de Ciprian Homorodean that brings together advertisements offering employment, in which the artist himself, Rumanian in origin, offers himself for a wide variety of jobs. And in this way subjects, such as the European immigration laws, self-exploitation and the insecurity that establishes no differentiation between qualified or unqualified jobs, are deployed.

Contrasting concepts, that go hand in hand with insecurity are entrepreneurship and creativity; the magical recipes, the big traps presented to justify this process of self-exploitation and culpability of all that doesn’t fit within the system. In his book, Paradojas de lo cool, Alberto Santamaría explains how creativity and culture are used to coat the logic of capitalism with a layer of sugar that makes it more appetising and addictive.

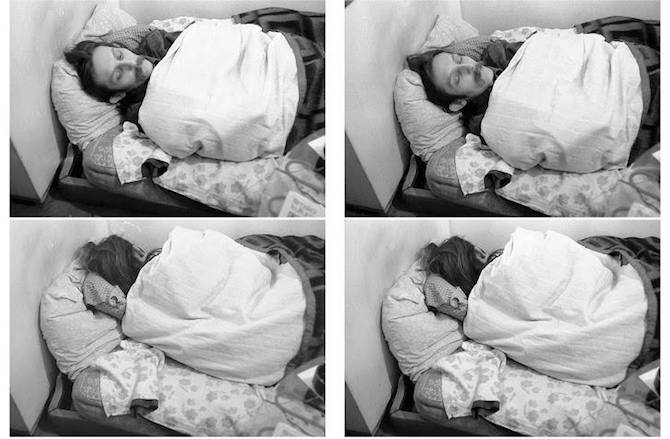

To identify these processes is the first step to being able to change them. Mladen Stilinovic, the recently deceased artist from Belgrade, did so in 1978 (and later in 2011), in his performance Artist at work, in which, wrapped up in a white sheet with his head resting on a pillow, he slept in a gallery. The idea is clear: the artist is an unproductive being within the dynamics of capitalist society. An act of resistance avant-la-lettre for the desolating future contemplated by Jonathan Crary in 24/7.

Montse Badia is member of AICA (International Assotation of Art Critics) , ACCA (Associació Catalana de Crítics d’Art) and IKT (International Curators Association).

www.a-desk.org

Independent Institute of Criticism and Contemporary Art, is dedicated to training, editing & research on contemporary art criticism.